The following questions and answers are excerpted from a conversation that followed the NBR screening of Freaky Tales.

This is a movie that shows real love for the Bay Area. Where did the story come from?

Ryan Fleck: Well, it starts with that Too $hort song, this really nasty song called Freaky Tales that I heard way too young, maybe nine or ten. I grew up with hippie parents. We had Beatles records and Janis Joplin and then my friends played me Freaky Tales and I was like, What is going on?! I became a Too $hort fan—of course, growing up in Oakland, you have to be. And being a ten-year-old kid in ‘87 and hearing that Sleepy Floyd game on the radio where Greg Papa is calling the play-by-play and he says, Sleepy Floyd is Superman, it always meant something to me that the underdog can still pull it off, maybe once. We had no business winning any games in that series against the Lakers.

I had been pitching Anna versions of a movie called Freaky Tales for years, right? Right. Most of them were pretty bad and not worth exploring here, but once we landed on the chapters I think things really opened up creatively.

The specificity creates the universality

Anna, you’re not from the Bay Area, so what drew you to the project?

Anna Boden: Like Ryan said, he’d been pitching me versions that I was not interested in for years. You know, he listened to that song as a ten-year-old boy! Well, he played it for me when I was a woman in my twenties, it did not have the same effect on me. I was not like, oh yeah, we gotta make this movie! I think what opened it up for me was when I started to think about it more from the young women’s point of view and listening to Don’t Fight the Feelin’ and hearing that song. Thinking about that, we created a fictionalization of an idea of how this song might have come to be and that’s what the second chapter is, into the Too $hort part of Freaky Tales and the underdog storyline. That got me excited. Then we started to think about like all these stories as being these underdogs overcoming the bully and that was the theme that pulled us throughout and that felt more universal. It certainly is absolutely 100% a love letter to Oakland and its culture, but it also had something that felt more universal to me.

There is something familiar about these locations and characters and themes that speaks to this specificity, but also this universality. Can you talk about finding that balance between those two?

RF: When we were writing the script, I wrote in all the places that I grew up going to—Loard’s Ice Cream shop, the Oakland Coliseum for sports, and Gilman, of course, Gilman, which I didn’t actually go to because I was afraid of the punk rock scene at that age. But I learned more about it as I got older and had so much admiration and respect for it. That first chapter is the closest we come to a true story in the movie, which is that they were being harassed by neo-Nazi skinheads around ‘87 and they stood up for themselves and they defended themselves and they had a fight out in front of their venue. The locations were key. And the Grand Lake Theater! I grew up going to movies at the Grand Lake, and we got to shoot there, and then we had a big screening there last week and the roof blew off the place. It was amazing.

Jay, you’ve worked with Anna and Ryan in the past. What made you sign onto this film?

Jay Ellis: First of all, getting the opportunity to work with Anna and Ryan. Seeing how they work, I felt super comfortable, and I really enjoyed the process. When this came around and I read the script, I was already in from a relationship standpoint, from a working standpoint. Then I got a chance to read the creative, and my mind was just blown. I couldn’t visualize anything that was on the page! I was like, how does this happen? What, how does he do this? And how do they do that? It was one of the most original things that I had read in a long time, and that got me really excited. I feel like part of my job as an actor is to fall in line with a filmmaker’s vision. I could very much see the vision and I understood that we were going to be dropped in a place in a time. Like you said earlier, specificity creates the universality because we know people like this in all these cities we live in. People who love their team and have their crazy sports moments. I mean, we were just outside talking about how Toronto was dead quiet when the Raptors won that championship because everyone was indoors watching that game. There’s someone in Toronto who will write their version of that game years from now. That specificity in this story really excited me and it was an easy yes.

It’s really interesting the way you treat action and violence in the film. What sort of conversations did you have about that?

AB: We started the movie as very grounded and in a very authentic time and a place, and we took the look from a 16mm doc-style Penelope Spheeris The Decline of Western Civilization style. We wanted it to feel very grounded. And then as soon as that fight starts, we wanted it to explode into another sphere and feel like, pow! You take the two feet that are grounded in reality and then have one of them fly off into outer space. There were little clues earlier, that this film had one foot in reality and another foot a little bit outside of reality. But for the people who hadn’t picked up on those clues, now everyone’s going to know that this is not totally grounded in reality. That came with that first moment of violence with the slingshot in the eye and then the blood splashing on the camera. We wanted it to happen that way because we wanted the violence to be fun and we wanted people to be able to laugh at it. We didn’t want it to really hurt. We wanted the neo-Nazis to get their due and for people to be able to feel cathartic about it, but in a safe way. So we can all applaud and have fun with it. The guy gets burnt, but then he gets back in the car, you know? That design has a bit of a comic book-y playfulness to it, but it’s still gory and bloody at the same time. So not comic book-y in a Marvel kind of way, where we didn’t have any blood, but comic book-y in a very different kind of way where we got to have a lot of blood!

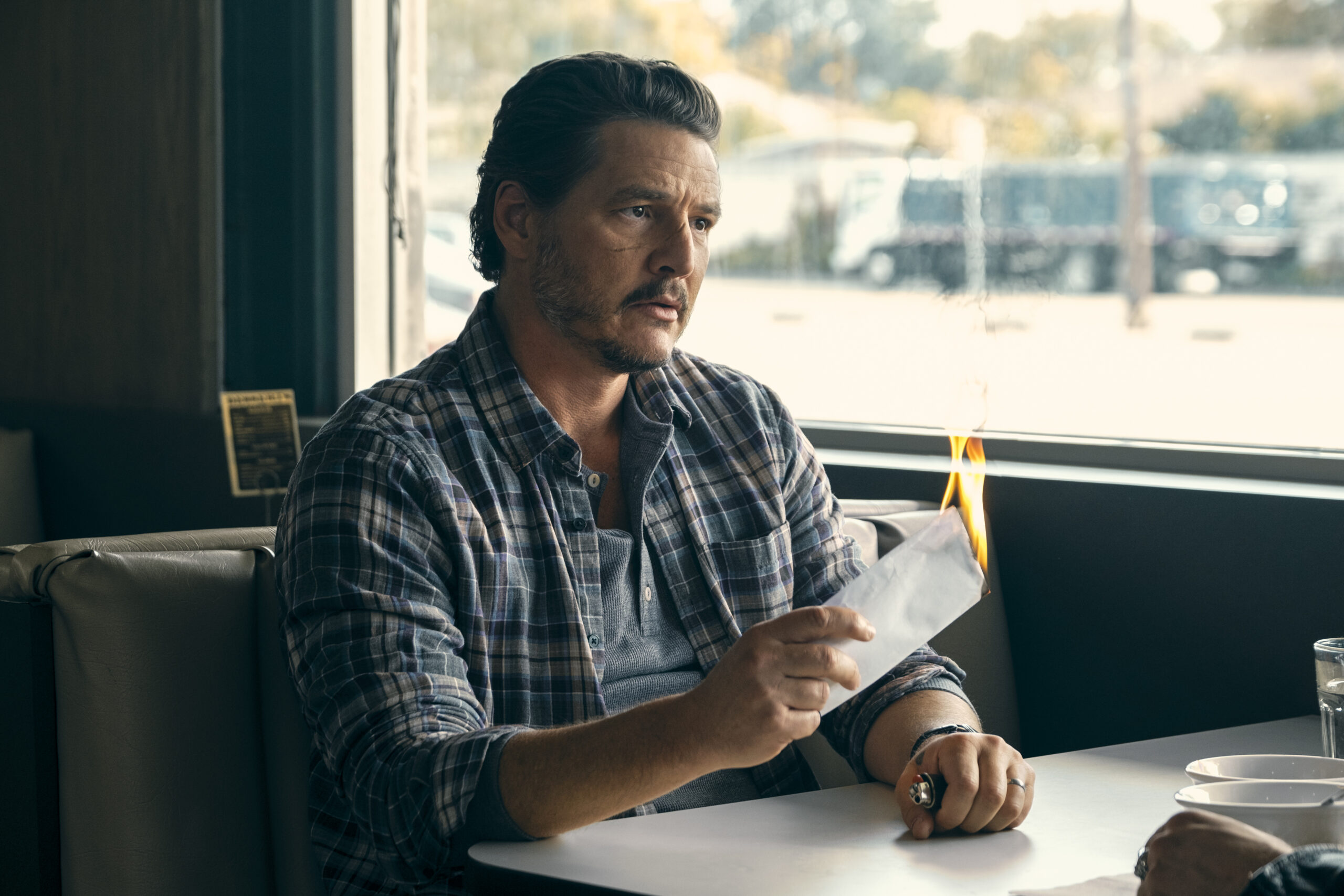

Jay, what’s it like playing a character that is based on someone real, but also a completely different version of him?

JE: Yeah, there’s obviously a fictitious side to his story. Ryan and Anna had sent over a couple interviews and specifically the interview that Sleepy Floyd did during that game or after that game. I remember watching it over and over again and trying to get the tilt of my head right and make sure my mustache was thin enough, and he has this big wide smile. I thought about the mannerisms and the physicality a lot. As we were going through the fight choreography, I pitched Ron [Yuan]—our stunt coordinator—that I wanted to do a crossover because Sleepy has this big crossover in the basketball game. So we do this crossover move and then we kind of work it into the choreography. It was this fun moment of trying to blend Sleepy’s quick, wide crossover into this fictitious side of him where he’s also this martial arts master who has all these weapons.

That was a lot of fun. There’s also this big monologue that I have as I walk down the stairs for the Psytopics commercial, and trying to get into his accent was also a fun thing to think about. I wanted to pay as much honor and respect to him because he has a record that still stands today, but then to also make the character very much my own as well. I feel like I got to do that a lot more on the fictitious side, while still honoring who he is as a person.

Could you talk about the collaboration with your cinematographer in terms of approaching each one of these four distinct stories in different visual ways?

RF: Like Anna said, we wanted that punk chapter to feel like a 4:3 ratio, with a grainy 16mm film look. By the end, we really go into anamorphic widescreen, like a Kung Fu movie or old Western. The path along the middle feels like traditional eighties cinema with some 1:85 aspect ratios. In terms of the colors, we wanted washed out for the first one, and when we get to the ladies in the second chapter, the colors are really popping with them and that was fun. Do you remember the specific conversations we had with Jac [Fitzgerald, Cinematographer]?

AB: We pulled a lot of different references from different films and photography and tried to pinpoint one thing for each chapter. I also remember us really struggling about whether we should go black and white for the third noir chapter, with Clint. But also knowing that none of our eighties references were black and white. We wanted it to have a distinct look, but instead we went distinct from the second chapter by choosing a very different kind of color timing and palette— a different color palette in terms of the clothes and the lighting. We tried to keep it more authentic to what our references were in order to maintain that consistency, even though there was this temptation to make each one look very different!