The following questions and answers are excerpted from a conversation that followed the NBR screening of It Ain’t Over.

When did you first start noticing a disconnect between Yogi Berra’s reputation and the player the stats showed him to be?

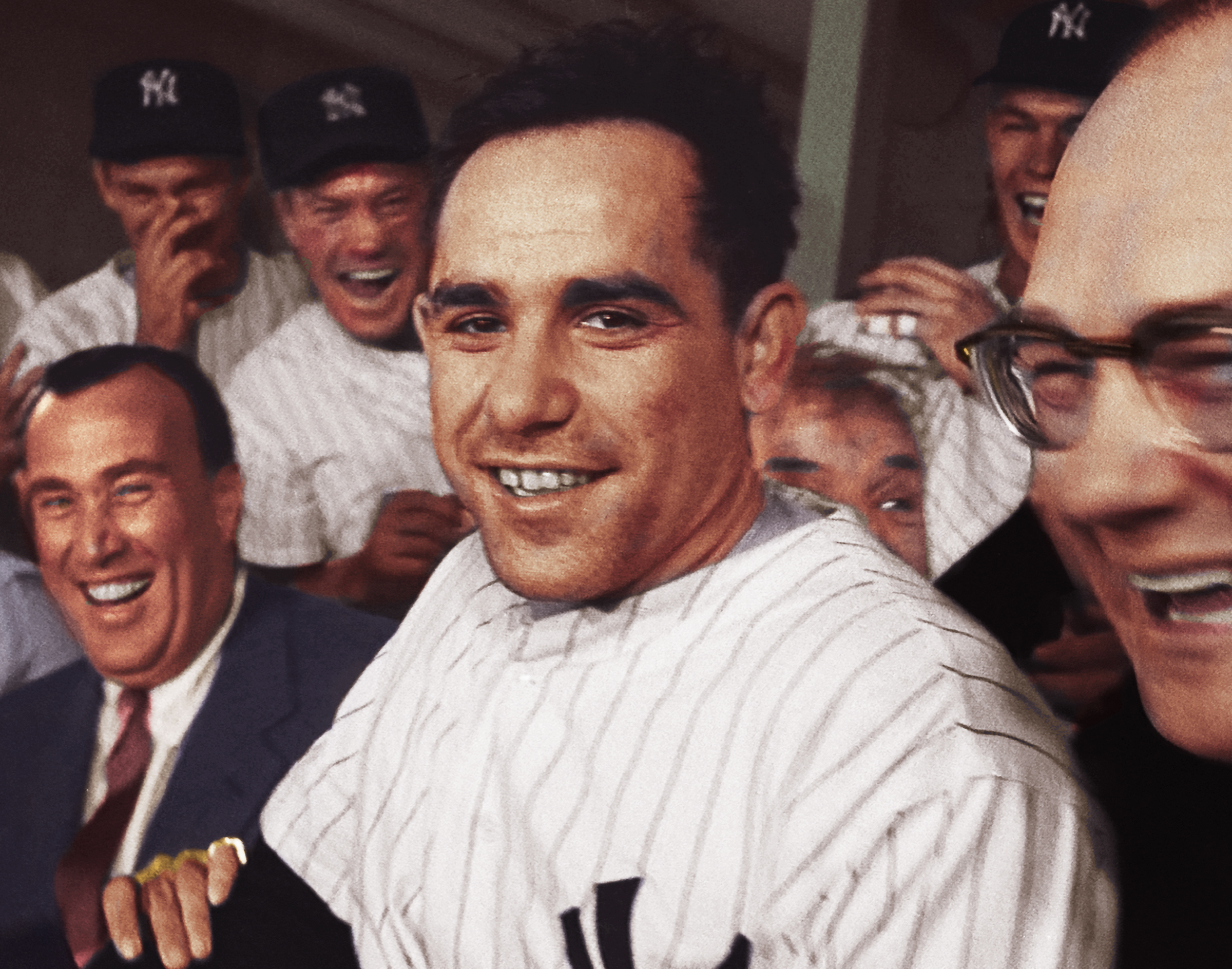

Sean Mullin: I think that’s what this was all about. When I started doing the research, I was like, wait, this guy was criminally overlooked. I mean, he was an incredible ballplayer and he’s not really talked about in a lot of the same circles as the greats. People always thought that he was good but not great. I think that there’s a difference between good and great. We really wanted to hit that home. The project came about because of Peter Sobiloff, our initial producer on this. He’s a big Yankee fan, and his wife dragged him to the theater to see the Mr. Rogers documentary [Won’t You Be My Neighbor?] in 2018. It was a Sunday, he was kicking and screaming, and as often happened in Peter’s life, his wife proved him wrong. He loved the movie. He absolutely loved it. And the next day, Monday, that’s when this project started. He went to the Yogi Berra charity golf event and he met the Berra sons. And he asked, why hasn’t there been a Mr. Rogers-like documentary about your dad? And they said, we don’t know. And then Peter told them, I have the perfect director for you. Peter had been a financier on Amira & Sam, my first film. He called me and said, would you want to direct a doc about Yogi? And initially I said, no, he’s too perfect. Where’s the drama? How am I going to get 90 minutes sustained on this story? And then I said, give me a beat. And then the deeper I dug, the more apparent this disconnect between perception and reality became. And finally, I was like, yes, yes, yes. This is the hook. Then I got the sons and we started shooting. The very first thing we shot was Dale’s book signing. He spoke about the drug abuse on the first day of shooting and that went really well and ended up in the film. I met Lindsay there too. I interviewed Lindsay a couple times like and every time she was like, you know, in 2015 I was watching that game with the “Greatest Players” with my grandfather and I said to him, maybe you should have been considered for that. She told me this story a couple of times so I said, how about we open the movie with this? We’ll use that as the hook. We’re not trying to say anything negative about Willie Mays or Hank Aaron or Sandy Koufax of Johnny Bench—they’re all icons and incredible players. But Yogi probably should have been in that conversation too.

I wanted to make a movie about a life well-lived

I read that you didn’t want to do a hagiography. Was that challenging given that the family was so closely involved?

They were involved in that they gave interviews, but we had full creative control and final cuts. I finally showed it to Lindsay and Larry when we were in the final cut stage, when we were almost ready to lock picture. We wanted to talk to them before we locked in case there was something really glaring. And they had two small notes, one of them was factual, a photo we had labeled wrong. We thought it was Yogi’s mom, but it was his aunt. The other thing—the problem with making a movie like this is that you can’t get everybody in there, right? Phil Rizzuto was one of the best friends. He’s hardly even in the film. It’s hard, you know, that was a difficult decision to make. But there were two people that Lindsay was adamant that we include. Gil Hodges was one of them. There was a quick Gil Hodges bit where he passed away and there was a funeral shot. And then there was one about Elston Howard too. We added a quick beat about him in the late editing stages. But yeah, other than that, if you don’t like the film, it’s my fault!

This is a guy where you can take any part of his life and make a full-length documentary about it. How did structure the film to fit everything in?

That’s a great question. I mean, I’m a writer at heart. I broke in as a screenwriter. I’m a proud member of the Writers Guild of America, which is obviously right now on strike. I make sure all of my documentaries are covered under WGA contracts. So this is a WGA documentary. But I’m not writing the interviews. The people are saying what they want. But I am writing the structure, I am saying, this is Yogi’s life. There are three acts, just as I would do in a fictional screenplay. And within those three acts, the way I write, I do eight sequences. This film is two sequences in the first act, three to four sequences in the second, and two in the third act. Each sequence is 10-15 minutes and each sequence is a short film, essentially. That’s how I write my fiction screenplays and that’s how I structure my documentaries. I look at this three-act structure and I label them. The first one is “Becoming Yogi” and the second one is “Doesn’t look like a Yankee.” I label each short film. For this film in particular, they’re even more pronounced because I demarcated them with those title cards, the ones with quotes from someone “super smart” along with the quotes from Yogi. And eight ended up being a nice number for the sequences, because that’s Yogi’s number.

What’s your relationship like with your researchers? I imagine that’s a very intimate relationship.

Absolutely. I have a production company called Five by Eight Productions, and it came about because as a comedian, I wrote all my jokes on five by eight cards. My house was cluttered with five by eight cards, and when my films started getting into festivals, I needed a name for my production company. And I was like, five by eight? I just looked around the apartment. My partner at the company is a guy named Michael Connors. He’s a co-producer on the film, and Mike is an Army vet like me. He went to Harvard and ROTC, an Army Ranger guy. We met at grad school at Columbia and we bonded instantly. And we’ve done all of our films together. When I work on his films, I do second unit stuff. We have an interesting production company where we’re both directors, so we both develop stuff internally. If his stuff gets greenlit, I co-produce, I’m like his creative, his right brain. And when I get something greenlit, he’s my kind of creative brain. So Mike Connors was a big part of this. He helped me with a lot of research and then there’s archival producers. I had four or five archival producers on this over the course of four years. It was just a lot it was a lot to go through. You know, I was very adamant that I wanted to tell the story as authentically as possible with as much footage as possible. I hope you all enjoyed the footage we dug up! It was a lot of work.

Do you have a favorite Yogi-ism?

Oh, goodness. I mean, I love them all. I like the ones that are more philosophical. I love that one where he said, “we’re lost, but we’re making great time.” That’s my life in a nutshell! And “nobody goes to that restaurant anymore; it’s too crowded.” It’s great. Those are some of my favorites, but it was tough.. We didn’t know where to put the Yogi-isms at first. Initially I had them in the third sequence right after the break. Baseball is only about thirty minutes of the film, at least with Yogi playing. I was very adamant that I didn’t want to make a baseball movie. I didn’t want to make a sports movie. I mean, I love sports and I love baseball, but I wanted to make a movie about a life well-lived and about a whole picture of the American Dream encapsulated in 98 minutes. I felt strongly that we had to get out of baseball as soon as possible. The Yogi-isms were initially going to open up the third sequence, but they just didn’t fit there. I moved them much later and they’re in the sixth sequence now. Stuff like that you have to move around a bit. The Jackie Robinson thing became such a meal, it became such a nice thing, that whole safe/out thing which I loved. And his relationship with Jackie was really great. They played minor league ball against each other. Yogi was in Newark and Jackie was in Montreal and they were both veterans. They really bonded over that. I really wanted to highlight that relationship as well.

Is being a Veteran a connection with Yogi Berra that you took very seriously?

Oh, absolutely. I mean, that is another connection. I was a first responder down at Ground Zero after the attacks of September 11th. We spent twelve hours a day down there. The first two weeks down there were really intense. And I was tasked I with escorting some of the remains out in bags and over to the morgue, I was in charge of that. So, dealing with that and finding out that Yogi was pulling bodies out of the water and after D-Day and Normandy, I was like.. I’m sorry, I don’t want to bring everyone down. But I did really want to really dig into that because I think that set the tenor for a big chunk of the rest of his life. He grew up very fast. And something we didn’t get into the film was actually some of the braver stuff he did. After Normandy, he stayed on. They went and had more battles in North Africa and he kept on going and fighting. That didn’t make it into the movie but the D-Day thing was so appropriate and people know about it. He didn’t know how to swim! And he really did think like, oh, rocket boats, is that Buck Rogers? He had this childlike wonder that was so great and I hope it comes through in the film. He had really tapped into some sort of universal truth, I like to say. He just had no filter. That to me was so fantastic to kind of delve into. I had a blast making this film, even if I was killing myself while making it. My mom says that I’m not happy unless I’m miserable. And I say, Mom, that’s a Yogi-ism.