The following questions and answers are excerpted from a conversation that followed the NBR screening of Moonage Daydream.

This film was created with something of a new genre in mind: the “IMAX music experience.” Can you talk about that decision?

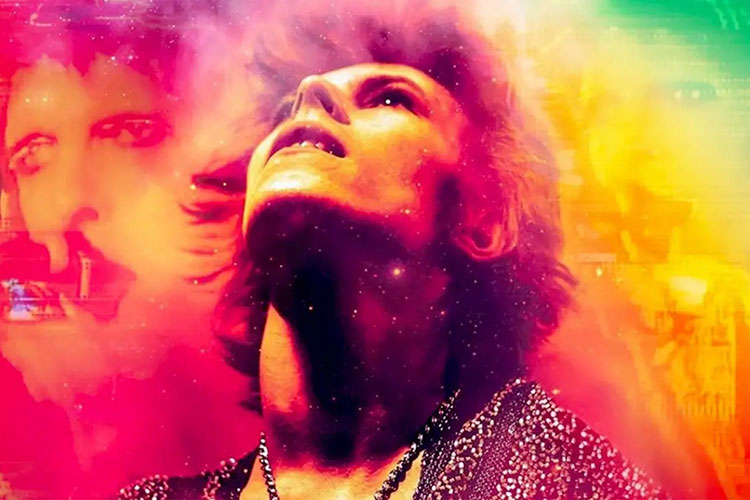

Brett Morgen: I have been doing biographical documentaries for the past twenty years. And when I finished Montage of Heck, I just… kind of feel like, for music documentaries… I love these speakers [gesturing around the theater]. I don’t think facts need to be delivered through these speakers! And so I got to this point where I wondered, “could I just take over an IMAX theater and create a musical experience?” And one that’s not biographical, but is instead almost like a theme park ride. And sort of have this intimate and sublime encounter with our favorite artists? And so that idea predated [this film]. I had this idea, coming off of Montage, to create this kind of genre, if you will. And, you know, what’s really difficult and challenging about that is the role that genre plays… we take it for granted. If you go to a comedy thinking it’s going to be a horror film, you’re going to be pretty disappointed. If you see this film thinking you’re going to get A-Z of David Bowie’s life… quit now, because you’re not going to learn anything along those lines from this film. There’s no names, no timelines, and… there aren’t even any album covers! So, you know, my feeling is, I don’t want to use cinema for that. The cinema is for stories. My films are always about, “what can I do that’s specific to cinema, that you can’t get in another medium?” Which is the experience. What’s the opposite of fact? Experience. So this started as a totally immersive kind of adventure, an experiment in sound and vision, and then I arrived at Bowie. And then everything changed. I mean, originally the plan was to have the IMAX music experience be forty minutes. So it didn’t really need to have a narrative included, it was just going to be a planetarium show! And then you extend it to feature length, and you realize the audience is going to get kind of freaked out after twenty minutes if they don’t know what direction they’re going. So this project really kind of evolved over time, from that original conception.

I was totally out of control. My life had no balance.

BM: Should I go full-circle to explain how it became what it is now, after starting with such a different idea? This is one of the things I’ve learned about David: Every moment is an opportunity for an exchange of ideas. I watched every frame in existence of David Bowie. The estate provided me with access to everything in their archives— it was the first time a filmmaker had been granted that kind of access, along with final cut. And then we collected all the material from outside of the estate. So we had everything: it took two years just to screen it all. I was my own editor. I looked at every frame in existence. And one of my favorite moments came when I was watching an interview with David in the ’80’s, with an MTV journalist… the journalist was not really versed in “Bowie-isms.” And you know, in the ’70’s, the rock journalists had the same cultural references as David. But in this ’80’s interview, he’s sitting down with this journalist and I’m thinking, “oh god… this isn’t going to go well.” And David is, like, talking to the journalist before the camera starts rolling: “Have you read any books lately? What have you read?” And he’s fully engaged with her. And he’s sharing some stuff that he’s just read… and it’s sort of going over her head a little bit. But I realized that David viewed every moment as an opportunity for exchange. So this is not my time; it’s our time (if I can borrow a little Bowie-ism). So… the estate provided me with everything. I don’t know what I was thinking, I decided to produce by myself, write by myself, direct by myself, and edit by myself! Someone recently said to me, “isn’t film a collaboration?” And I just said… “uhh… yeah but…” You know, you get this film if you don’t collaborate. This film is very personal. And it got very personal for quickly. Shortly after I got this assignment — or after I gave myself this assignment, I should say — I had a massive heart attack. And I flatlined, and was in a coma for a week. This was at the very beginning of the project. January 5th, 2017. My daughter and David share the same birthday, January 8th. A year to the day that David died, I was in a coma. And it was severe. Like, my wife showed up at the hospital and they told her, “he’s not going to make it, call everyone, it’s over.” And when I woke up, when I regained consciousness, within the first few words out of my mouth to the surgeon were, “I need to be on set on Monday. I’m directing a very important pilot for Marvel, it’s called ‘Runaway’ and I need to be on set on Monday.” Of course the doctor told me I wasn’t going anywhere. And I said, “you don’t understand! It’s Marvel! I have to go!” And my wife was terrified. She could see that even a major heart attack couldn’t quell me. And two days later, I pulled the plugs out, I drove over to ABC, and went to auditions. I was totally out of control. My life had no balance. I have three kids— my youngest would give me Father’s Day cards with messages like, “thank you for showing me the work ethic.” You know? That’s great, I had a cardiac arrest at 47. What sort of legacy is that? And I really started pondering these questions. What was the infinite pearl of wisdom that a dad would say? And I didn’t have it. And it was from that point of view that I began the two year dive into all of Bowie’s media. And as I was getting into it, I realized that Bowie was offering me a roadmap to how to lead a more balanced and fulfilling life. And that in the event something should happen to me, I could leave this film to my children so that they can always go to it and find the answer. Because I do think that it is almost like some sort of religious text: ways to live your life, according to Bowie.