The following questions and answers are excerpted from a conversation that followed the NBR screening of Attica.

In my view, this film tells a story of oppression that many people don’t want to hear. This film has been in the works for many years, can you talk about its development?

Stanley Nelson: I was about twenty years old when Attica happened, and living in New York. Like most of the country, I was transfixed listening to what was happening day to day and then heartbroken and devastated by the end. When I became a filmmaker, I felt that there was a story that hadn’t been told and had so much more to tell us. I’ve wanted to make this film for over fifteen years, but have been thinking about it for more like forty years. A couple of years ago with the proliferation of cable channels and different streamers, we thought that it was the time. We were able to raise a little money and create a trailer, a little five-minute piece, and Showtime bought in. At that point it was all systems go.

Traci A. Curry: Then Stanley asked me if I was interested in working on the film, and I didn’t know too much about Attica except for the basics. But I knew the film would get involved with ideas of justice, human rights, the prison system, and the way that all of those things are wrapped up with power and race and class and the themes I’m always interested in exploring. It was really exciting to have the opportunity to dig deeper into the story.

We wanted to be treated like human beings.

What were the challenges in finding people to speak to you and the levels of interest?

SN: When we started making the film, out of the former prisoners that were alive, there were many of them that were pretty young when it happened. It happened fifty years ago, so there should be a number of them that we could find, that would be seventy or seventy-five years old. That was the thought going in. But I’ll let Traci talk about the nuts and bolts of actually getting people involved.

TC: My goal was to get every single person that was still surviving that was there when it happened and who could talk about it from personal experience. We went about that in a variety of different ways and had some terrific advisors. Then it was a matter of going through records. There were years of litigation after the re-taking of the prison and all of that is public record. Many of the men—Mr. Harrison, as well as others—were on record having told their stories in court when the settlements happened. Some of it was reading through those hundreds of pages of documents, figuring out who might still be around, who might still have a story to tell. People who were of an age at that time meant that it was likely they’d still be around. Then it became the work of tracking those folks down. Picking up the phone and calling someone out of the blue to ask them to recount this horrific and traumatic event to a complete stranger… maybe Mr. Harrison can jump in to explain what that was like. But I did understand going into this that it was a profound trauma for a lot of these people and that it’s no small thing to be cold-called and be asked to recount that experience, especially with no idea of what they’re going to do with that slice of your life in their story.

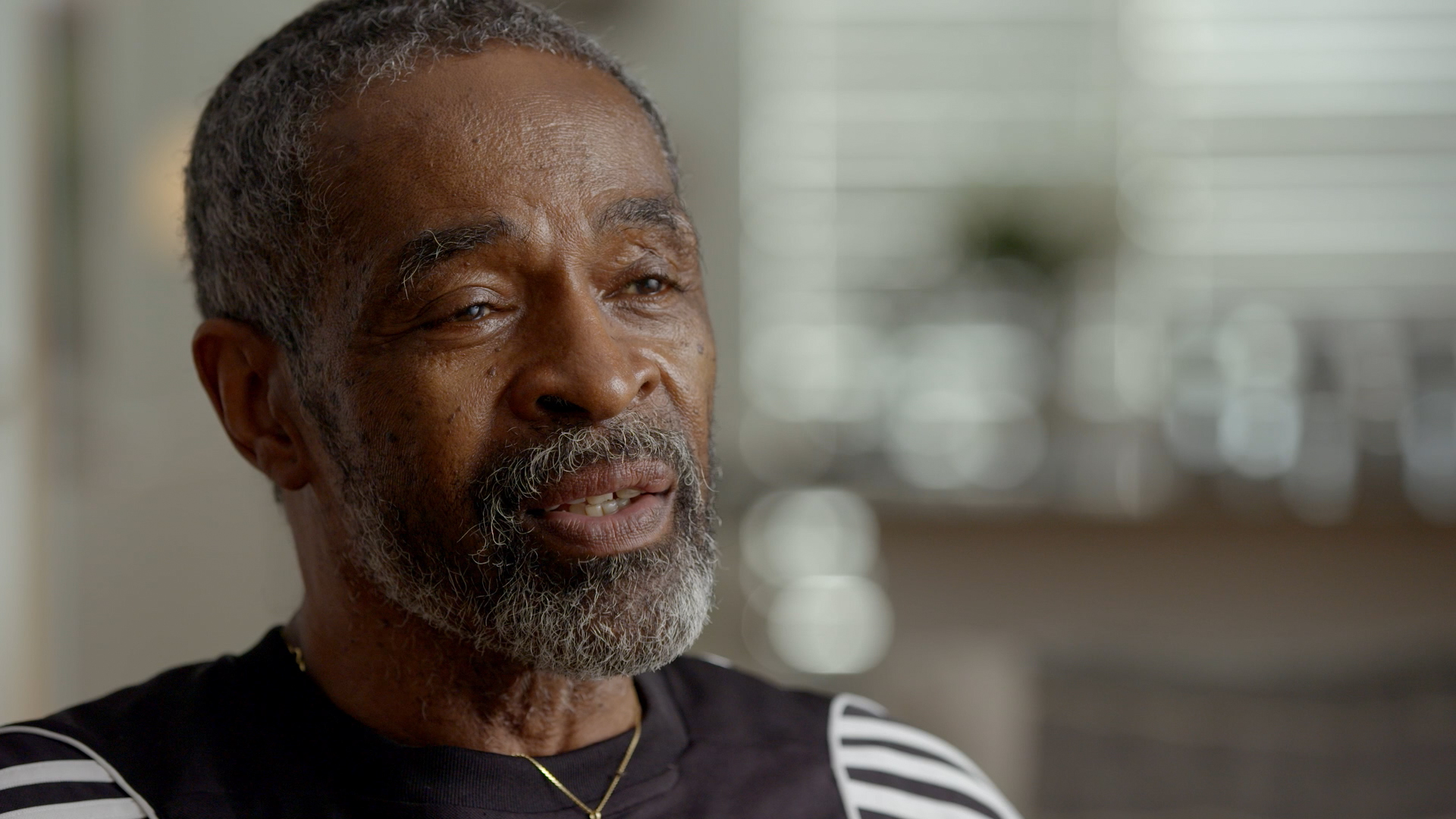

Arthur Harrison: At first I was reluctant and didn’t want to be involved because after all these years, until the young lady called me, there was no one concerned about what happened to all the other brothers up in Attica. When I say brothers, I mean Black, Hispanic, White… it was everybody. We had become of one. We wanted to be treated like human beings. When the young sister called, I said, well she’s too young to really understand about what’s been going on. I spoke to her a few times to feel her out, and then she called back again, so I could tell she was really interested in doing this. Most of my life, I’ve been a fighter, a trained fighter, so this is my way of fighting back. In that event at Attica, we couldn’t fight back. We didn’t have the opportunity to fight back. As a kid, I was always taught not to show signs of weakness, like tears or crying. We men weren’t supposed to do that; that’s the way I was trained because I was in the system quite a few times as a young kid. This brother and this sister worked magic because what I saw last night at the screening was real. This was like therapy for me, because I don’t know of too many brothers that got into real therapy… they gave me parole but they never sent me to a psychiatrist to get help for the trauma. All these years I’ve been carrying this baggage. Brother Nelson and this young sister here have given brothers like myself the opportunity to vent and give our version about what happened.

So Mr. Harrison, was last night the first time you saw the completed film?

AH: The full completed film, yes. What really hit me in the core was when they had all the brothers naked. It reminded me of movies I used to watch that had guys being shipped over here from Africa. That’s the same type thing, like slavery all over again. I always used to look at prisons like that. Jewish people would call them concentration camps, and I call them plantations. I still see them like that—even more so now—because I’ve been through this hell called Attica. I’m here today to speak for the brothers who can’t speak for themselves, like LD Barkley, who spoke so brilliantly inside Attica about what occurred. My last moment of seeing LD was being dragged through the yard of Attica, asking not to be hurt. We heard gunshots, and I then didn’t hear LD’s voice anymore. More than likely, that was the time they took his life. Because he spoke out, and he spoke up. But all LD was talking about was anyone who had any mindset of wanting to be treated like a human being. And they took his life for that reason.

This idea of these people not being treated like human beings really comes through in the film. As filmmakers, how did you keep that as the focus?

TC: I think in some ways, the style of the film followed the substance. What I mean by that is whenever you’re doing this historical storytelling, the instinct is to set up the context, and get some talking head experts to tell us what it is that we’re seeing instead of letting the story unfold by itself. Initially we played around with some ideas like that… let’s talk about the environment outside the prison and what was happening in the world, since it was during Vietnam. What became apparent as we began to move through the process of doing the interviews with the prisoners and also with the families of the guards, is that there was nothing stronger or more compelling than their own voices. That naturally lent itself to creating a film that allowed those voices to shine through, and it’s right on screen. Really, our job was to get out of the way and give them the space and the time to tell the story as they lived it and as they experienced it, and the end result is what you see there in the film.

SN: As Traci said, the humanity of the former prisoners that we interviewed just shines through and you can’t deny it. By listening to them talk, you get an insight into their personalities… one guy is funny, one guy is thoughtful, and they’re all human beings. One of the weirdest questions that I’ve been asked by one journalist was “why didn’t you put in there what crimes they committed,” and my answer to that is that it’s not relevant to the film. That’s not the point. As people say over and over again in the film, the point was that they should be treated like human beings regardless of what they were in there for. In some cases, their demands were really small, like to be given toilet paper, visiting rights, rights to call home. Small things. They were just demanding to be treated like human beings. And they deserved to be treated like human beings.