This film has a different editorial pace and perspective than you usually portray in your films. Would you be able to talk about your approach with these older men in the film?

Martin Scorsese: This is not a film we could have created or made as effectively if we had tried to make it ten years ago. It’s a situation where, like Robert’s character says at the end of the film, you don’t know what time is until you get there. Not until the kids are running around you and worried about you do you have that vantage point. From that perspective, when I read Charles Brandt’s book and Steven Zaillian designed the script did it come together. We went back to the audio recordings of Frank Sheeran. With all those elements, we deduced it was all about memory. Memory is often in flashes, but I was always fascinated at why a slower paced picture is effective. I always remembered Val Lewton films and not seeing everything being the reason it is effective. Or learning again a language of movie making or movie narrative through a slower paced Antonioni which for different reasons, people did not find that accessible in their lifestyle but found it accessible through the film. It is about learning patience with the work. It’s patience and timing. Yes, over the years we have had a lot of excitement and enthusiasm and bursting energy, as part of my makeup; I can’t help that. And the humor is very important, but ultimately over the years, I could not connect, and I think it is bourgeoisie lifestyle, over in Japan, France and here too. And at a certain point I was not interested because there were worse things going on in the world. The thing about it, ultimately, the Ozu pictures when you start to look at them, something happened. Over the period of 20 years ago and earlier is when I began to appreciate the use of inserts and the objects that are photographed. I do still have to put myself in a frame of mind to watch one of those films. I have been in Taiwan and other places, where I see something on Television and I say that looks like Ozu. He’s peeling an apple for 20 minutes and it’s really good. Why am I looking at that? There is a series of small essays by a Japanese author from I think the 17th century called “Essays in Idleness” which has this tone of the film. It deals with life and it deals with the passage of time and how dying is a part of living. Ultimately, it’s like reading Nabokov’s autobiography, “Speak, Memory.” He talks in his autobiography about a memory of light coming through a window when he was a small child. These sorts of things are the memories that stay with us, for whatever reason!

I could have shot for another six months. It was just great.

How did you live inside Jimmy Hoffa and figure out who he was through your very internalized performance? Who was Jimmy Hoffa to you?

Al Pacino: First of all, I had the help of these two great artists, so that was comforting. It’s just that age is part of this, as well as the things you learn and find out. I’ve worked with Bob before, but I only appreciated Marty and what he has done, but have never worked with him. This was a wonderful opportunity, so that helped a lot. Going into the question, to me I have to understand him on my own actor’s terms and try to interpret him. I also had to find him within myself. That is the long complicated story of the actor and the actors work throughout the years. It is to try and find different ways to try to get to something and make it alive and relevant to oneself. There is so much data on Jimmy Hoffa. They were in the process of filming for weeks before I hopped on the project, so it was almost necessary for me to get the research, although actors always use research. There is a certain gestation time where the information needs to be absorbed, and I had so much help here. At the same time, there was all this data, and I watched it, took on some of it in, tried to understand some of it, and find what I would say to him, which would probably be different from someone who knew him very well. It had something to do with his love of something, and his need to somehow be behind something, which was the union and the connection to it. It was that sense of righteousness in him that is understandable when you think of his background and the poverty he came from and the fighting for the rights of the people who did not have wealth. He was sent away to prison and what did he do? He formed groups and tried to help people. When he saw what they were living through, he knew. That aspect of him I related to. The machinations of his life, I don’t know much about them, but he had to take up whatever kept him going. That’s all there was to it. There was a reality and it was real, and although he had the power and believed in it, he was not doing it for the power. He connected with the people he felt connected to in some way. They came from the same kind of background, but he was not mob person.

Mr. De Niro, you are the one who found this book. Is the film as you visualized it? You also do so little and say so much in the performance; can you speak to that?

Robert De Niro: Marty and I were doing another movie. It was kind of like a popular hitman type of thing, but it was not the same thing. Then Marty started showing me the movies of Jean Gabin and Jacques Becker. So then I was saying I had to read this book I had been aware of for a couple of years. I first became aware of it with Eric Roth about two years earlier and he said you have to read this book while we were editing The Good Shepherd. So I said let me read it for research. Then I said to Marty you have to read this. When he read it, he said this is more of what we should be doing.

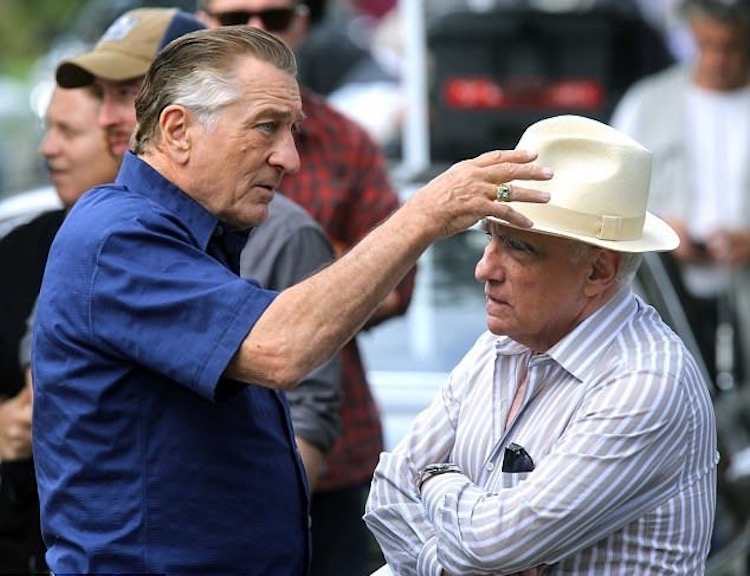

MS: Also, me and Bob had been trying to make a picture together since 1995. So that was 24 years we had not worked together. And we kept trying to meet up but we kept missing each other. He would be involved and I would be involved. It ultimately came down to what Bob felt when he read the book and what you thought of the character Frank and the situation of his life. He had a strong connection when he presented the idea to me. I immediately felt we could tap in and go with it.

RD: I felt it also had a greatness and grandness to it. It had these historical characters that had died in ways that we still haven’t actually found out how they died. But there was enough in the character of Frank Sheeran. Personally, I believe what Frank said. There are others who might not, but I do it as Marty says. This is the way we tell it. It’s like Jake LaMotta. At the end of the day, we interpret it how we felt.

In this film, there are so many scenes where the characters are not saying what they actually mean. They don’t say “go kill this guy. I know he’s your friend, but oh well.” Can you talk about how you play those scenes?

RD: With Marty, it’s great because we were all so lucky to have the time to do it in the way we wanted to do it. I could have shot for another six months. It was just great. Marty would allow us to try anything, and if he thought it was not right or it was going off track, he would say direct it this way. It was this terrific experience allowing you to explore those subtle things, because you don’t have to do very much to convey something. Nobody understands that better than Marty. That is what it’s about.