The following questions and answers are excerpted from a conversation that followed the NBR screening of Tully.

How did you go about conceiving two characters who would ultimately converge?

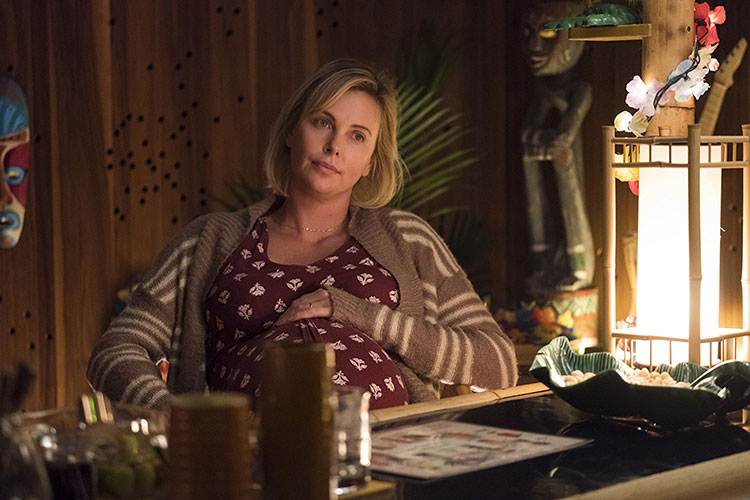

Jason Reitman: I always thought of the movie as being like those lenticular posters, where if you look at the poster and you kind of move your head two inches, the image changes. And the fun of this movie was making a film where in the closing moments, you realize you had actually been watching two movies at once. The trick was kind of feathering things in with Mackenzie’s character so that you could go back and watch it a second time and all of a sudden you start to notice all of these details about her parents and where she is on screen- how we edited and shot it. Starting from the fact that you know the first time she walks up she knocks on the door, the second time she seems to mysteriously have a key, the third time now she’s just coming in from screen left. It continues into body language. Scenes start with Charlize sitting in a very specific position in a specific place in the room, and by the time the scene ends, the cameras return to that place, and Mackenzie’s now in that place and Charlize has left. Wardrobe was a big thing. We talked a lot about it. The first time we meet Tully, she’s always wearing things that Marlo would have loved. So they are all reflections of things that Marlo has worn. It was an infinite amount of detail, and we spent a lot of the shoot building that.

“It was a cross between being at a summer camp where Jason’s the head counselor and a family trip to the lake house where Jason’s the dad.”

How did you work together to develop these parallel characters?

Mackenzie Davis: We didn’t really do that much in the beginning. I had some concerns or ideas, and thought that I wanted to echo mannerisms or things that Charlize did. And Jason really wisely talked me out of that. It really just became about the relationship and anything that echoes in Tully that is Marlo, I think comes from the script.

In making this film, were there things that you realized about your younger self? What would you tell your younger self in your current state?

Charlize Theron: Oh… it was so long ago! I guess the idea of just having someone who gets it. Somebody who understands exactly what you’re going through and is completely empathetic to the struggle that you’re in. I feel like in my twenties, I was so rushed. I felt like time was running out. I felt like I couldn’t do it all or do everything. And I don’t think I quite enjoyed every moment. That’s the one thing about my twenties. I wish I kind of just stopped and enjoyed the space that I was in in that moment. I do that so much better now in my 40’s.

JR: If you look at Juno, Young Adult, and this movie, they all deal with the concept of time. That’s actually kind of a natural thread through them. One thing my dad taught me about storytelling early on, was to always remember the difference between your plot and your location. It came from a moment when he asked me to come over to his house one day and watch Kiefer Sutherland’s 24. I went over and I watched a few hours and it was really good. And I said, “Why is this show so good? There are so many TV shows about terrorism. Why is this one is so great?” And he looked at me kind of incredulously and said, “Well this isn’t a TV show about terrorism. This is a TV show about a man trying to save his family.” Terrorism is a location in that show. The way that we use teen pregnancy in Juno, the way that we use parenthood in this film, are really locations to talk about a different idea which is, what is it like at that moment when you have to turn a chapter and you start to think of your younger self as literally a different human being? And what if you could actually, at point that you needed to, get a chance to say goodbye to them? It’s Diablo’s creation. But I think that’s part of her genius. She doesn’t make her movies about the location. She uses the location and it makes it very real and then kind of feathers in what it’s about. And because of that, you’re always surprised by it.

Ron Livingston: A current that runs through this movie with all of the characters is the human, desperate, need to be seen. The mother thing is kind of an overlay because mothers are overlooked. Really its about a person who nobody sees, so she has to make up somebody that sees her, and its none other than herself. The first step is you have to be willing to see yourself as the person that you actually are, versus the person that you thought you would be or you have some fantasy of. you have to let go of the imaginary person who is the facade and actually see and appreciate the version that is really there. And then once you do that all of a sudden your husband’s able to see you for who you actually are. And it turns out that that’s the person we’ve been missing all along.

Can you elaborate on the idea on seeing yourself more clearly through your children?

JR: My daughter is 11 now and I see the things are kind of intimidating to her. I see all the things that she’s thinking about. We have the same eyebrows– they’re heavy. Even when she was a four year old girl, they would always betray her and just give away everything she’s feeling. It becomes this lovely mirror and it makes me feel like I can mind read her. It does allow me to re-evaluate all the things that were coursing through my brain as a kid.

What what makes a Jason Reitman set special? What does he do differently from other directors?

CT: It’s a very strange thing to try to explain. But there is something about Jason that is very much alive in me and I feel like there is a lot of me that is very much alive in him. When we first met and thought about working together, there was an element of like, “we’re going to have nothing in common.” Sometimes Jason knows me better than I know myself. It’s a very strange thing to say. I know. From the first moment that we worked together, we had a shorthand with each other, and there’s something about us on a set that is just really well matched. I feel like a lot of times when you make a film, it’s like a relationship. You have to kind of meet the other person halfway in the middle. It’s not always exactly what you wanted for an actor or for filmmaker or where you are. You have to always be ready to put your own process aside in order to have the other person have some room to do what they need to do. And for some reason with Jason, I don’t ever feel like I have to hold anything back or make room for anything. It’s like we just fit. We have the same approach to rehearsal. We had the same approach to direction. The same approach finding character, talking about character. The same approach about shooting. I’m just grateful for it, and I hope we get the a lot of movies because it is hands down my favorite work experience.

RL: It was a cross between being at a summer camp where Jason’s the head counselor and a family trip to the lake house where Jason’s the dad.

MD: Something I love about the way Jason directs is I know some directors only talk about casting, and I think that it’s great, but I also like being directed and it’s part of the experience to have somebody pay attention to your performance and then give you some small actionable notes. And Jason was so deliberate and nuanced with his direction and it was never just for the sake of coming in between scenes, but would give the perfect comment that would put you on the brink of tears right before you started the scene. It’s just a lovely sense of understanding of the character, and how everybody worked, and of the story that we were telling. It was so nice to be led by somebody who understood the world so much better and deeper than I did.

There are several great montages in the film, and sometimes that can seem like a crutch, but here it is seamless. Was that seamlessness found in the script, direction, editing, or all of the above?

JR: The montage was really tricky. It was on the call sheet every single day. We were just adding to the list, because it wasn’t in the script. We started just asking each other what are real details from being a parent that we can add that we haven’t seen in a movie before and we started asking the cast and crew. And we created a questionnaire that we gave to 10 mothers and said, “Just give us as much detail as you’re willing to share.” And they were unbelievably generous with their experience. That’s what the cell phone came from. That was a new one for me.

How do you feel this film is going to echo in the world?

JR: One thing that I really love about the way the Diablo wrote this, is there is a lack of specificity about certain things that allowed the movie to broaden up and be accessible to anybody. They prevent the movie from being clinical. And they make the movie more emotional. And one of the ways is that we are not specific about what’s happening to Marlo. We’re not specific about what’s happening to her son Jonah. I think it’s more important to all of us that we echo that idea of feeling lost. That there is this moment as a parent and it happens over and over where you feel a certain shame for not knowing what to do, no matter what a good job you’re doing. You’re pretending that it’s a blessing. That it’s perfect. It’s the greatest thing that ever happened to me. It is all those things but simultaneously you’re not supposed to talk about the fact that it’s terrifying. It scared me. It makes me feel that I don’t know what I’m doing. It makes me feel like somehow I’m failing my child. As if I didn’t get some rule book that clearly everyone else did. We over diagnose and are constantly over diagnosing. And it is a movie where one step after the next, she’s forgiven. At first by herself and then by her son saying, “Maybe we don’t need the brush. I just I just like being next to you.” And so, what I hope is not for a specific conversation but just conversation in general. So I hope every car on the way home that comes from this movie has a different and unique conversation that reflects what is actually happening to the people inside the car rather than the people that were on screen.