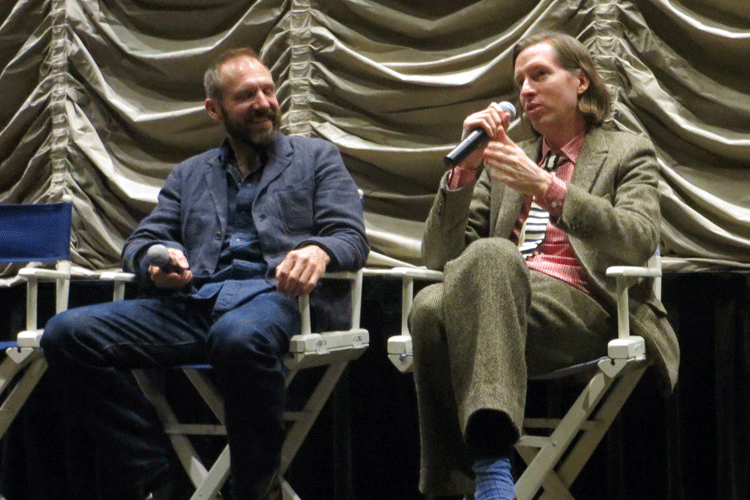

The following questions and answers are excerpted from a conversation that followed the NBR screening of The Grand Budapest Hotel.

Talk about the inspiration for this piece.

Anderson: There’s this writer Stefan Zweig, who I had never heard of up until six or seven years ago. I read Beware of Pity – which I loved – and I thought about trying to adapt this book. But then I read more of his fiction and I kind of liked many of the pieces, and then his memoir, The World of Yesterday, ended up inspiring the whole setting of the movie. So I ultimately decided to do something Zweig-like, instead of adapting only one of them.

You and your co-writer based the main character on one of your friends. So much of the film is fantastical, but there are shades of the film that are very real.

Fiennes: So much of it was real to me. There’s this friend of Wes’s that I know and who was the model for Gustav, but I think a lot of Gustav is Wes and Hugo’s imagination, and we developed him between ourselves. He can be quite scathing, very fastidious, slightly vain, he can be funny, he loves his poetry. In fact I improvised all his poetry, but he (Anderson) cut it out.

Anderson: It’ll be good for the blue-ray! This is very rude in fact, but Ralph was always very good with text, and he has to recite all this poetry. But the poems in the script get chopped off where I stopped writing them, and Ralph always continued on and gave me a couple extra stanzas. In the earlier cuts of the film they went on, and you were very good at improvising poetry.

“In that moment, I knew I had to get Ralph in a movie. Just seeing him do Shakespeare on a sofa.”

Is it correct that you wrote the piece for Ralph?

Anderson: I had wanted to do something with Ralph for years and years and then we met and got to know each other over the past three to four years. Ralph had shown me a sort of mood reel for the film Coriolanus, and he did some of the speech, and in that moment, I knew I had to get Ralph in a movie. Just seeing him do Shakespeare on a sofa. We didn’t really think of any of the casting until the script was done, except for Mr. Gustav. We had Ralph in mind, and were hoping he’d be seduced into doing it.

Fiennes: I’m very easily seduced.

How many of the locations were found and how many were sets, and what was the process of designing the look?

Anderson: It’s all on location. With the exception of miniatures, we didn’t do any shooting in a studio. The big lobby of the hotel is a department store, a big turn of the century period department store. We built the walls that enclose the atrium, we sort of built everything in, but these vaulted staircases and stained glass ceilings, that’s all real. And that’s the way most of the sets were done. We’d take a real place and build some things around to adapt it. I like that way of working – discovering an element of it on location and still designing it too.

Can each of you describe a favorite on-set experience?

Revolori: In the scene we shot right after the prison breakout, Harvey Keitel comes up to me ands says “Good luck kid,” and he slaps me. It was a real slap. And, I didn’t know what was happening because they had talked about it in the prison before, when I wasn’t present.

Anderson: And it shouldn’t have happened that way, it wasn’t right. It shouldn’t have been sprung on you.

Revolori : It gave me such surprise, I think that really came off and it was great. And then about 42 takes later, we finally cut. The thing is Wes very much likes to say “One more. Just give me one more.” And for this scene, he didn’t even give me that false hope. He would say, “Alright give me a couple more!”

Fiennes: I remember, we had an amicable tussle over that line of Wes’s, when you see soldiers waiting in the snow for the train, and what you really got is me and Tony sitting on a little thing on wheels, and you’ve got a window frame, but nothing else, open air. We’re very cold and it’s very snowy. And there’s this little trolley with our profiles, and a cutout window through which the camera sees the soldiers in the snow. It’s all very precise. And I have a line, “Why are we stopping in a barley field?” And I say to myself, There’s no barley. It’s snow. Why do I say that? So Wes goes “No, no, I think it’s okay. The word barley field is kind of funny.” Okay, I get it, I get it, but can I just kindly say something else while we’re here? So I have this line, “Why are we stopping in the fucking wilderness?” Also funny. I just remember it being really cold and just obsessing about this line. And now, no one questions it, of course.

Anderson: When you first saw the movie, I was sort of watching like, oh no, now he’s going to see how I used the takeaways of the barley scene.

Fiennes: There’s no barley! A wonderful and blissful learning curve was that I bring a quite predictable actor’s sense of “where does this come from,” which sometimes is helpful. But you can dream in Wes’s imagination and his specificity and his unusual take on stuff, and I treasure that, because you carry this thing in your head, this thing that you’ve all just seen, and I think that’s why so many actors come and want to be part of it. Because as actors, you really value directors who are able, in a difficult climate, to do the film they want to do. So, please invite me again.

Anderson: Not to keep getting on the barley field, but the thing is there’s a reason why I thought there’s no one else who could play this part but Ralph. There are others that could do “a take” on this role. When we had a conversation like that, it reinforced that there was no one else that could make this feel like the real guy, like an authentic real person.